Uncle Stan, the Hip Hit Record Man © Martin Gavin 2006 & 2011

I'm excited: I'm about to meet Stan Lewis. Uncle Stan 'The Hip Hit Record Man' as bluesman Lightin' Hopkins called him on record, is partly responsible for a very large chunk of the back catalogue of soul and blues to come out of America during the 60s, 70s and 80s.

He is, quite simply, one of the most significant figures in the history of blues, R&B, and even Northern Soul, but receives little recognition compared to Atlantic's Ahmet Ertegan, Berry Gordy or Lewis's old friends, Phil and Leonard Chess. Funny how history picks its heroes.

He formed Jewel Records in 1963 in Shreveport Louisiana, his hometown. The label was named after a chain of grocery stores in Chicago that he saw from the passenger seat of Leonard Chess' Cadillac. These are the Jewel supermarkets featured in the famous shopping-mall car-chase in the film, The Blues Brothers. In the 1960s heyday he had 120 staff including 12 promotion men on the road and his own printing shop. Maybe not Motown, or Chess, but they do things differently in the South: more relaxed.

The interview has been set up by my friend, Bill Bush, writer and performer of the Northern Soul rarity, 'I'm Waiting'. The location is Lee's Lounge, a blues and live music venue on East King's Highway, Shreveport, Louisiana. I would later find out that it's now the only club in town with regular live music, crazy when you remember this where the famed Louisiana Hayride was based just about two miles from where I'm at now, in the grand Civic Hall, a venue where Elvis cut his teeth as a live performer.

Lee's is a busy, old style 'tavern' a bit like Huggy's place in Starsky and Hutch and the blues jam that's taking place is just what you want: genuine blues players including Bill Bush and an appreciative audience of all ages set in a dark, smokey (no smoking ban at the time) atmosphere that adds to the buzz.

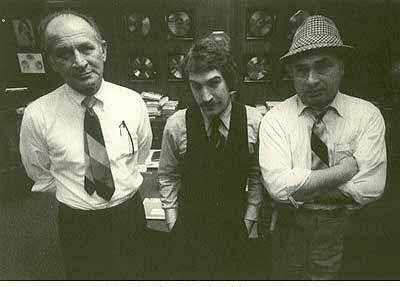

As soon as he walks in I know it's him. The only photo I've seen is at least 50 years old of Stan with his ex-wife, Paula (of the label) standing with Elvis, who looks about 16. Now he wears a white suit, shoulder length white hair expertly styled and alligator shoes, who else could it be.

I later find out that a serious car accident in 2002 left Lewis with arthritis and some other associated injuries but despite the fact that many details about his career have faded with time, he is a sharp dressed character in his late 70s and every inch the Southern gentleman that his appearance suggests. He also turns out to be a rich vein of information and stories about the golden age of R&B.

After the introductions we take a table in the back of the club and I asked Stan how he got started, which takes him back much further than I expected to the Great Depression and a nine year-old entrepreneur with a news stand. "I got a corner news stand and sold magazines, we also had a veterinary next door and I cleaned the dog pens, during the depression things were tough and money was scarce," he says. "I sold papers until I was 13 and in the morning and afternoon and business took off. I remember the extra edition coming out when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbour and after that there was an extra edition almost every day, which suited me."

Lewis got more and more rounds delivering newspapers and had accumulated $2500 when he got married at aged 17. His next step up was slot machines and aged 18 he bought five 10/50 Wurlitzer jukeboxes, "The kind you see in all the movies," and five pinball machines. It was around this time that he started to look for a reliable source of blues records because his main location was Bossier City, a blues (Black) area. "It was big bands, swing and jive that was in demand," he says. "I had to go to HL Green, Woolworths, etc. to find the records to put on the jukeboxes."

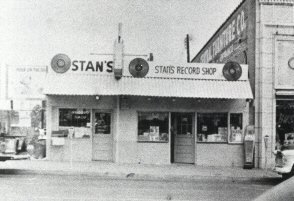

It was on one buying trip that Stan happened upon one of his most significant breaks. "In 1948 I visited J&M Record store to pick up the latest blues records and the shop happened to be for sale, for exactly $2500, the amount of money that I had saved. I'd been married just under a year and I told them that I'd pay them $1800 and that I wanted to but some inventory - they agreed." It was located at 728 Texas Street in Shreveport and his wife originally worked in the store while Stan worked other jobs to make ends meet. Eventually, they did well enough with the records so they could buy a slightly larger store next door and expand the business.

"I got rid of the jukeboxes because I didn't want to be in competition to the jukebox operators as I was also selling them by this time in East Texas, Arkansas, Alabama and even Oklahoma and had a big jukebox clientele. I was the first person to give the operators a 10% discount on the records that they bought, which they weren't used to getting and I really built up a very substantial business selling jukeboxes and records to go into them."

Stan speaks in a low, calm Southern accent like a smoother Bob Dylan, it's a pleasure to listen to, although hard to make out clearly at times. "One day, Leonard Chess pulls up outside my place, this would have been mid 50s, and he was sharing the trip through the southern states with a guy called Lee Agulnick. Leonard was pushing a record by Muddy Waters and Lee was plugging a record called 'Long Gone'. Leonard would come through Shreveport about every three months when he had a new release out. Well, I had a contract at that time on Sonny Boy Williamson, which I gave to Leonard and that would prove very good for both of them of course. Leonard covered the South and Phil the North, he took Waxy Maxy up in Washington and Joe in New York.

"Phil stayed in the background but he was pretty sharp, and then Marshall came along. Later on Leonard put in some real good people around him, that was his skill, people like Dick La Palm. Dick was Nat Cole's manager and set up Argo for Leonard, the jazz label."

It was common for record pluggers to drive around and distribute their records personally, bearing in mind that Chess was little more than a well established 'start-up' business in the late 40s trading as Aristocratic Records, eventually becoming Chess around 1950.

As well as the varied back catalogues of Jewel, Ronn and Paula, the three labels that Stan Lewis set up in the 60s, he produced or co-produced many tracks around this time he tells me, including Lowell Fulsom's blues standard, Reconsider Baby, and sat in on recordings by Muddy Waters, Sonny Boy Williamson, Etta James and the Moonglows, to name a few.

Lewis was gradually gaining status and his position as one of the most important distributors in the South was cemented when 1949 he was invited to Chicago as a guest of the Chess brothers, staying at Leonard's Chi-Town home. "He was 12 years older than me and always called me kid," says Lewis. "We got real close and the records that I was distributing for Leonard saved my business in the early fifties, it was tough. John Lee Hooker's Crawling King Snake, I'm In the Mood Hobo Blues, Charles Brown's Trouble Blues got real hot here and Leonard would introduce me to people, mention my name. Leonard was a diamond in the rough, a very special person."

Although never rich in the Berry Gordy sense of the word, Stan, a key Motown distributor in the South, was able to loan the label 'some cash' when Gordy wanted re-sign Stevie Wonder in the late 60s. He's still bitter about losing 60,000 units of stock in Stax, which he received in the late 60s after selling up his own company. A two year cooling off period before resale meant that Stax went under before Stan could sell and he lost around $2.4 million by his calculations, and his masters. He blames his lawyers for not seeing it coming, although ironically they also had Stax stock. He also makes reference to a British business man, publisher and music collector well known on the UK soul scene of the 70s who never paid him for masters, but best not to get into that one - bit too close to home.

Lewis is still grateful for favours he received from industry giants like Chess and Gordy back in the day. "Guys like Bob Shad, who later went to Mercury, he had Lightnin' Hopkins and Peppermint Harris, who I released on Jewel in the 1960s with some great stuff. Jo Bihari of Kent and Modern was also very good to me, I remember that Ike Turner was riding with him on the second trip through here and then he was always with him and would give me samples and started selling direct to me, I got real close to these guys, Ike was crazy, but he lived, ate and slept music.

"In the early 60s Leonard Chess asked me to come up to this convention in Chicago and he would take me along and put his arm round me and say, 'This is my man Stan, take care of him,' and I tell you, that opened doors. Great days, I was very lucky you know, I remember going to Sun, Stax, Hi, Fame, all these places and sitting in on sessions. I saw the Rolling Stones record their sessions at Chess in Chicago at 21/22 South Michigan, and Muddy Waters, the Moonglows, Etta James, on yeah, I saw them all right there in the booth. I love the doo-wop sound personally, The Moonglows and The Clovers were great."

It was the late 50s and Lewis was by now selling records mail order. A young Bob Dylan was a customer and Lewis remembers marvelling at how "this kid" could afford a long distance telephone call. He would later receive a signed biography from Dylan with reference to this period and to thje importance of Stan's shop.

"I had started to buy time, about 15 minutes of airtime, on KWKH in the afternoon and these guys were real happy to get their records played because stations didn't play what they called race records at that time in the 50s. Because I bought the time I could play what I wanted to play," he chuckles. "In those days you couldn't own more than seven radio stations, so it was a very independent industry with great diversity, not like today."

That may be true, but his choices didn't sit well with the good ole' boys of Shreveport and Lewis, a Roman Catholic, soon found himself on the wrong end of a pillow case, as it were. "It's a funny thing, I got the first Fats Domino records and Jimmy Reed on the show, that was the first time Jimmy Reed was played on a white station, Baby What You Want Me To Do. After that The Klan put posters on my door and I was scared to death I'll be honest, I've never told that to anyone before, but these people were very prejudiced and very violent. You see, I was raised in a black neighbourhood, I knew the people - we had black neighbours and I'd play with the kids and we got along very good with the black people in town, it wasn't as bad as people think."

The Klansmen didn't stop him, and soon Lewis was buying airspace on KWKH and KAAY in Little Rock, Arkansas, which was a more powerful station, and WLAC in Nashville.

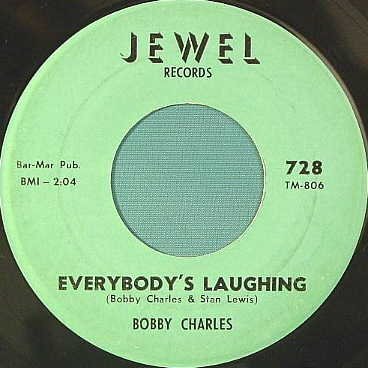

Fortune smiled on Stan and his family during the 1950s with the emergence of blues and R&B as a mainstream, crossover music form his mail order and shop sales business flourished. He guided sessions for Dale Hawkins' hit, Susie Q, and Lowell Fulsom's Reconsider Baby in Dallas in 1963, already a music business veteran although just in his early 30s, he formed his own label with Bobby Charles as his first artist, cutting Everybody's Laughing in late 1963. "Bobby Charles was a great writer," says Lewis. "I gave him to Leonard (Chess) after that and wrote some great material for Fats Domino.

"I would go along to sessions, although I didn't really know much about the engineering side of things I learned a lot from Jo Bihari and the engineers of course, you can't run the whole show yourself you need good people around you. A lot of people don't admit that but I some good engineers and recorded at some great studios, Universal, Chess. Being in the retail business you get a feel for the music and soon you get to love it.

"My mail order business was totally R&B but I was selling white music too; country too and had Arista, 20th Century, United Artists, Cameo Parkway as a distributor. They put out everything from jazz to R&B."

By 1963 Lewis had the record store, a mail order business and his own Jewel label.

The legendary Jewel Records was followed by subsidiaries Paula (after his wife at the time Pauline) and Ronn (after his brother, who Lewis credits as his 'right arm'). I asked Stan why he had Ronn and Jewel, both hosting R&B stars (Paula was his pop label). "Well, the thing then was payola, if you had too many records on the same label you got accused of payola, bribing the DJs. That was why Leonard had Checker, Argo, etc. and Atlantic had Atco, Modern had Kent, etc. I was never involved in that type of thing.

"The record industry was so interesting, exciting there was something happening every minute, I mean every minute 24/7, you'd get the records in, run them down to the radio stations then the show and the mail order. I remember one night I was at Leonard's house and at 2am the phone rang. It was the Cook County jail asking if he could come and bail XXXXXX (a certain very famous female R&B star) out of jail, which he did."

"When Atlantic came along I got their first blues record to distribute. I also had the first Stax release and I got the first Motown release. I became the biggest distributor in the South. John Richbourg was also doing well with Ernie's record shop who took airplay as well, he was involved with Joe Simon and played him to death on the show. I came on after him and played at 1 o'clock in the afternoon, that was how the music was made up and we would get a lot of free records, that's how the game worked."

Stan's company was in many respects pioneering, cutting innovative business deals that would be copied across the music business in the late 60s and 70s. He approached Bob Smith at KCIJ (later to become the fabled Wolf Man Jack), to negotiate a PI deal, which he explains meant Payment Per Inquiry. For every call that Stan received from a potential customer, Smith got a cut. The radio station was based in Del Rio Texas but the transmitter was a massive 250,000W unit in Mexico. "It was probably the biggest transmitter in the world," he says. "I started to get orders from Europe, in fact everywhere bar the Soviet countries, really everywhere else.

Through strong sales and a reputation for business Lewis became sub distributor for many of the major labels such as RCA and Decca. "We were shipping records worldwide eventually, it got real big." Lewis was given 10% of the Chess pressing plant in Chicago when the company moved to 2120 South Michigan Avenue. When they opened another plant in Nashville he got 10% of that one just for being great at what he did, that was the way it worked. He had helped the Chess bothers get established in the south, he had given them Sonny Boy Williamson, he was in. Motown also pressed at the Nashville plant and most of the other major labels of the 60s.

Through his contacts, basically the founding fathers of modern popular music, he travelled the length and breadth of the USA, often as a companion of Leonard Chess. "Leonard had a big station in Chicago and E. Rodney Jones was a key figure there, a DJ. Then he moved to Baton Rouge, he was great and I could call him and say, 'Man I need some help with this,' and he'd play it for me. The other guy was BB Davis at KOKA who would sometimes pay a track four, five times in a row if he liked it."

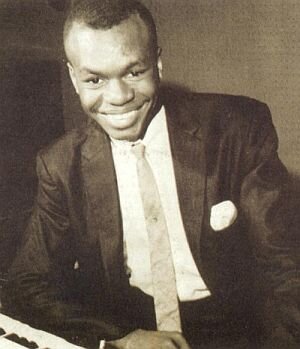

The standout for me thing about talking to Lewis face-to-face were the stories behind some of the tracks that I've loved for years. One of these concerns Toussaint McCall's stunning Southern Soul ballad, Nothing Takes the Place of you. The story about McCall's visit to Shreveport was confirmed to me later in the week by BB Davis, the DJ that Lewis refers to above.

"I remember one night in the record store I was closing up and this guy knocked on the window," says Lewis. "Well, this good looking negro fella was waving a record at me, it was an acetate if you know what that is, like a metal master. Anyway, I was tired and I knew my wife was expecting me home so I told him I was closed but he wouldn't go away so eventually I let him is just to get rid of him really and played the track. Now I don't know if it was 'cause I was tired or what but it didn't do anything for me, he made me play it again but I wasn't really interested, it was just a real simple little recording and I was used to cutting tracks at Muscle Shoals, Chess, Stax you know, really top end studios. Anyway I thanked him, and I think I must have said to him 'take it to BB at the station'.

BB Davis was one of the first successful black DJs in Louisiana and he took up the story when I met him later that week. "Stan didn't dig the track," says Davis. "I was playing my show and it was near to quittin' time when this guy tapped on the window, cause the station had a window to the street in these days. I let him in cause he had a record with him and said I'd listen. Man, it was Nothing Takes the Place of You and I just melted, I thought it was heartbreaking man, and I played it at least six times, plugging it over and over again.

"Almost straight away the phone started to ring, 'Who that, where can I get it man, does Stan have it?' They just kept callin'. Toussaint explained that the record was recorded in his living room at home, then he left and headed back home."

Stan Lewis remembers what happened next: "My phone at the shop started to ring off the wall, the girl asked me if I've ever heard of the track that everyone was callin' about by Toussaint McCall, Nothing Takes The Place of You, luckily he'd left a business card and I grabbed my cheque book, a contract and took off on the highway to Munro after Toussaint. I caught him and singed him right there at the roadside and that was how the track was released as the third single on Ronn and became a hit."

The prolific releases from the trio of labels during the 1960s made Stan successful. National and international hits by John Fred (Judy In Disguise was Stan's' biggest seller), blue-eyed soulsters, The Uniques (USA), and Northern Soul heroes, The Montclairs, plus the local blues and pop hits, meant that when Chess Records sold up in the late 60s Lewis was in a prime position to take on many of the artists after the company that took over Chess went bankrupt.

"They knew me, guys like the Blind Boys, the Soul Stirrers, Ted Taylor, Fontella Bass, Lightnin' Hopkins, I took all these guys from Leonard. Artists were always in debt though, they always borrowed ahead of themselves. The late John Fred owed me $45,000 when he left the label, even after his hit and Little Johnny Taylor, who was very successful, owed about the same too, they were always living above their sales and that's still the same today I think."

In 1966, Lewis started a gospel singles series (the 100 series) on Jewel, and followed that with the establishment of Ronn Records in 1967 (named after brother, Ron), as an outlet for R&B and jazz style recordings.

He turned down offers from the majors to buy the labels in the 60s, something he regrets. Enigmatically, he also regrets selling eventually in 2000, mainly because of the subsequent resurgence of blues as a mainstream music form and the boost that CDs and downloading provided. "I felt that I could conquer the world in the 60s, I wasn't ready to retire because I was still on my way up. However, things changed in the 1970s - I stuck to the R&B but I really would have been better off selling."

Lewis sold to a large .com but he states that it never came to anything and that Len Ficco has the label now, but he admits to being unsure what he's doing with it. Lewis is retired and after the accident is not as "frisky" as he used to be, in his words. However, right at the end of the interview he drops the news that he has unreleased masters of Lightnin' Hopkins, Ernie Johnson and some 'other things' in the can and would still like to get back into the business, taking advantage of the latest technology to go right back into the music business.

Not everyone likes Stan. I've spoken to several well known characters over the years from that part of Louisiana, including Elvis's band members, who are less than keen on Lewis. You don't run a business like Lewis's without making enemies, but I have to admit that I found him charming, self effacing and very genuinely proud to have achieved what he has done over the years. When all things are taken into account, I reckon Uncle Stan 'The Hip Hit Record Man', founder of Jewel records, is a diamond geezer.

©Martin Gavin 2006 and 2011

Can catch the author Martin Dj-ing @ Friday Street in Blackfriars, Bell Street, Merchant City, Glasgow on Friday 25 March 9pm - 3am.

.

-

1

1

Recommended Comments

Get involved with Soul Source

Add your comments now

Join Soul Source

A free & easy soul music affair!

Join Soul Source now!Log in to Soul Source

Jump right back in!

Log in now!