Everything posted by Blake H

-

Jesse James

- Retro-repro Usa Concert Posters For Sale

These sound great R+K, and I've found the very thing to put them in..... https://www.wilkinsonplus.com/invt/0242498 I've been looking for some frames for a while for my posters & pictures and these are really good, trouble is I need about 60 more BH- Kenny Williams - You're Fabulous Babe

Correct me if I'm wrong (I usually am!) wasn't the demo titled Your'e Fabulous GIRL and changed to babe on the back of the advert? BH- Jab Label ?

- Vibes On Classic Northern Tunes

Frank Polk "Love is dangerous" Capitol, classic vibes intro BH- Running Away From Love

Likewise, top event bar none Just ordered the CD with "Send your love" on at https://skipmahoneythecasuals.com/index.html BH- Temptations - Stay. 7inch Price Anyone Please?

I bought one at the Bass for a tenner a few months back, think it was the crossover night too cheap? nahh!! BH- Running Away From Love

You've quite a habit of breaking Skips tunes Mr H, what was that great track you played at Pitches? Blake- Dj's Running Over Their Times

A certain "Older" DJ has this off to a tee, with ten mins left he'll say "another six from me then over to...... works every time BH- Mid - Week Venues

Leeds had The Peel on Boar lane on Monday nights, thursday it was The Cellar Bars under the Corn Exchange and another Monday night venue was Heaven & Hell on the Headrow, this was a night club complete with bunny girl waitress's and an aluminium dance floor . Happy days Blake H- The Hostage - Donna Summer

What about Al Martino 'Charmer' on Capitol? Got to be up there BH- Unbelievable

- Us Retro Concert Posters

/index.p...mp;#entry346720 This old thread might help BH- Rca Stock Copies

Have you got a Judy Freeman (Hold On) tucked away Alan? BH- Vala Regan Fireman

Quite a few red Atlantic demos on the bay at the moment. BH- Lee Miller

Get well soon Lee and then you might like to settle up with me and start afresh. Blake Helliwell- Love Committee - Tired Of Being Alone

John, is that the one that came in a deal we did a few years back? There is a slight chip in the playing surface and the writing is blue felt tip pen. If it isn't there are two, my old copy (now out there somewhere) came from Memory Lane Records when they were in Morden Best Blake H- "rare" Cd Compilations Wanted

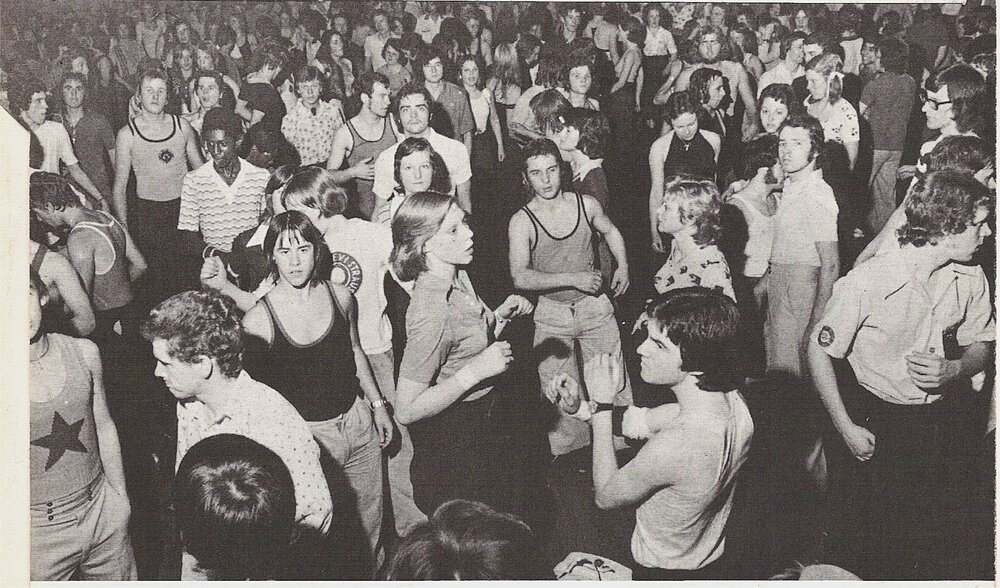

I'm looking for Volume 1 to 5 of the "Rare" series of Compilations released by RCA & Ariola in 1990 on CD only and the first Soul Souvenirs comp (Columbia) also on CD Many Thanks Blake- Casino Photo

Just sorting a few records and came across the (in)famous "Footsee" on Pye Disco Demand and wondered if any of the people pictured on the sleeve are Soul Source members, or can you put a name to a face. Only one I think I know is Steve Caesar (the black guy!) correct me if I'm wrong. Best Blake H- Playthings

They can all run round to mine as I've got quite a few Disco Demand demos if anyones intrested, and Playthings YDJ..... PM me. Blake- Wand 70s Releases

Nice bit of Wand memrobillia........... https://cgi.ebay.co.uk/SCEPTER-WAND-RECORDS...2QQcmdZViewItem Blake- Tolbert - I Got It (rojac) Strong Vg++

Still sounds like a Real Thing outake to me.............takes all sorts I guess. Good luck with the auction Blake- Bad Accidents With Rare Records?

You're right Ian, I've dumped clothes before now to get 45s in the suitcase, after all clothes are replaceable!! Blake- Collecting 60s Us Capitol 45s

- Mike Charlton On Soul Discovery

Nice follow on from Shaun Robbins as well BH - Retro-repro Usa Concert Posters For Sale